Hypothesising a Retail Investment Instrument with Public Goods Funding Integration

Trinity Morphy lays out his idea for a solution to the funding shortfall for ecological and social impact projects relying on public goods funding.

By Trinity Morphy | November 21st, 2024

Traditional public goods provide the basic infrastructure for innovation in any society and are usually funded by the government and public-private partnerships. Without them, societies would labour all their lives paying private market mechanisms to access resources like roads, public health infrastructure, public parks, etc. Similarly, Web3 public goods provide necessary components and services for ecosystem development. They are usually funded by the foundations of the ecosystem in which they function and other ecosystem projects.

Ecosystem-specific goods are dedicated to a particular ecosystem. In contrast, ecosystem-agnostic goods function across different ecosystems and are usually funded by both ecosystem projects. The latter has grown to accommodate Web3 initiatives geared toward achieving net positive ecological and social impact. These initiatives are reliant on grants due to the difficulty of commercialising their impact. Although the Climate Coordination Network consistently comes through, there’s not enough money to sustainably grant these projects.

Instead of relying on altruism to raise PGF money for this category of projects, this article discusses the development and use of a PGF-integrated investment instrument (PII). PIIs hold the potential to provide sustainable funding for impact projects over a long period, especially given their potential to compound and scale with more capital inflow. Although PIIs are long-term shots, they might be just what we need to end the constant battle of profit vs. impact for impact builders.

Understanding public goods

A public good is a commodity or service that has two key qualities: non-excludability and non-rivalry. Non-excludability means everyone can benefit from a public good without restriction once it is provided. National defence protects all citizens regardless of their contribution to its funding. Non-rivalry means that the consumption of a public good by one individual does not reduce its availability for others. One person's enjoyment of a public park does not diminish the ability of others to enjoy it as well.

Public goods exist for the efficient collective functioning of society. This emphasis on collective functioning is the reason why governments, not the private markets, mostly provide public goods. The latter will restrict the provision of the goods to only those who can afford them since their utmost priority is profit-making. In contrast, the government makes it available to all income classes through public financing and taxation.

A real-world example of this is public health in Nigeria. Only high-income earners can afford proper healthcare because the private markets control a major chunk of the health sector. The percentage controlled by the government has deteriorated to the extent that although it is affordable, low-income earners now resort to self-medication and traditional medicine.

State of public goods funding (PGF)

Although we have discussed traditional public goods and its funding mechanisms, my focus for this piece is Web3 PGF.

The concept of integrating PGF with web3 was formally established by Vitalik Buterin, Glen Weyl and Zoe Hitzig in their 2018 paper titled Flexible Design for Funding Public Goods. Same 2018, Kevin Owocki experimented with Gitcoin which later spinned off the Gitcoin Grants program that regularly distributes grants to public goods through community participation and signalling.

So far, Gitcoin has facilitated the distribution of over US$60 million to 6000+ projects in PGF. Optimism has distributed over US$150 million to 250+ public goods in its ecosystem. Ethereum Public Goods have received over US$240 million from the Ethereum Foundation. The Solana Foundation has distributed over US$250,000 to 30+ public goods. Cumulatively, web3 public goods have received over $500M in funding.

Web3 public goods can be ecosystem-specific, like Zora of Optimism. We also have ecosystem-agnostic public goods, a category most ReFi projects fall under. Although projects focused on creating net positive social and ecological impact are not necessarily public goods, it has proven nearly impossible to generate revenue through their operational model without severely limiting accessibility to those that need it most. This challenge has made these projects totally reliant on grants leading to their public good-ification.

Understanding the problem

If there was enough money to just go around, relying on grants wouldn’t be a bad thing. As it stands, however, there isn’t enough money available for projects to have a meaningful ecological and social impact.

The Climate Coordination Network has funded 200+ projects with over US$4 million. This is just 1% of total funding ecosystem-specific public goods have received through network fees and support from other projects. This funding pales in comparison to the ever-growing problems these regenerative public goods are constantly tackling.

This leads to the big question: Why isn’t there enough funding?

Reliance on altruism

The Climate round distributes matched funding through algorithms that prioritise individual donations. Although this is not a linear indicator, more individual donations equates more matched funds. Because of this, projects capitalise on the altruism of prospective donors to get more donations. The problem with this method is that it is less likely to work on non-regens. Not everyone cares deeply enough to donate to projects striving to regenerate the world.

Donor fatigue

Recurring donors are getting tired of donating especially when there’s no glimmer of self-sustenance for most projects donated to. Some have become desensitised due to the overwhelming scale of problems needing attention. This emotional exhaustion can lead to a reluctance to support projects they once cared about. I know a few people that completely stay off social media during climate rounds due to the constant shilling and over-solicitation.

Small matching pools

Impact PGF entails larger donors providing matching funds for distribution. A grantee can receive matched funding anywhere between US$50,000 to US$20,000. This wide range exists because matching funds are small (between US$100,000 to US$250,000) compared to the number of projects they’re usually distributed to (between 100 to 200). To distribute equitably means that some grantees will get bottom-range funding which may not go anywhere in operations.

The funding scarcity affecting social and ecological projects limits their scale of impact, which so far is a speck in the amount of work needed to counterbalance extraction. However, this problem has motivated the development of various solutions like Generos to draw in more capital. Given the continuous persistence of the problem, there’s much crisscrossing of tools and ideologies to be done to facilitate greater capital inflow.

The PGF-Integrated Investment Instrument (PII)

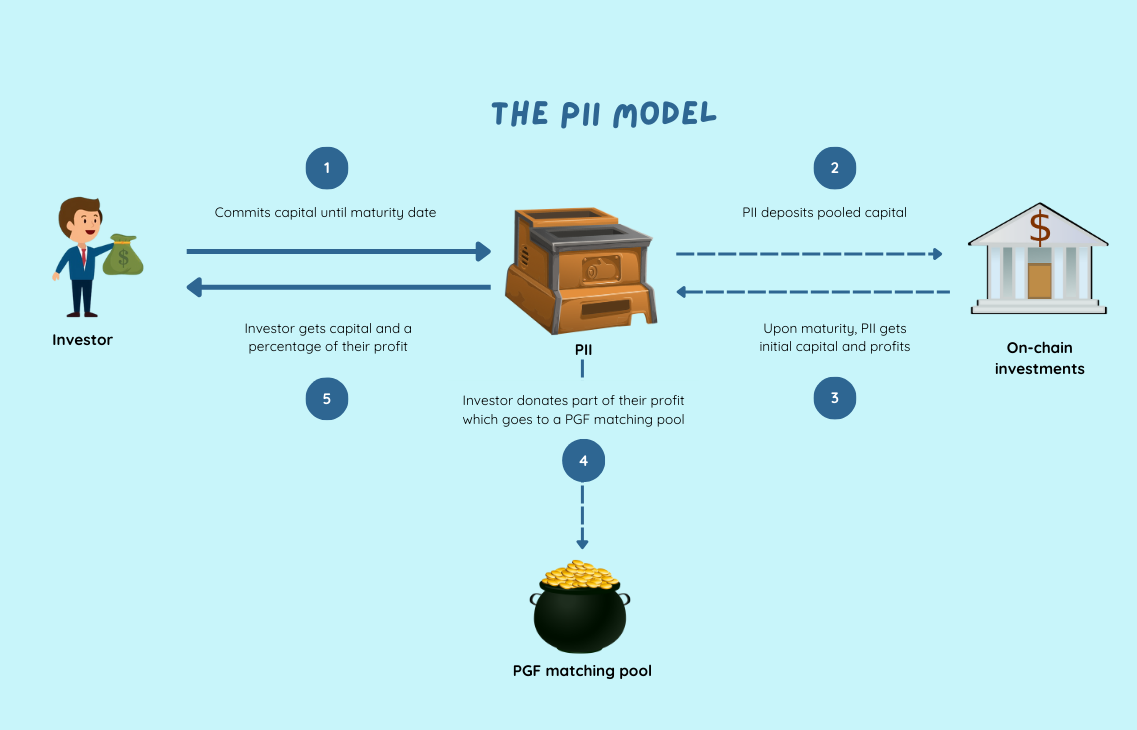

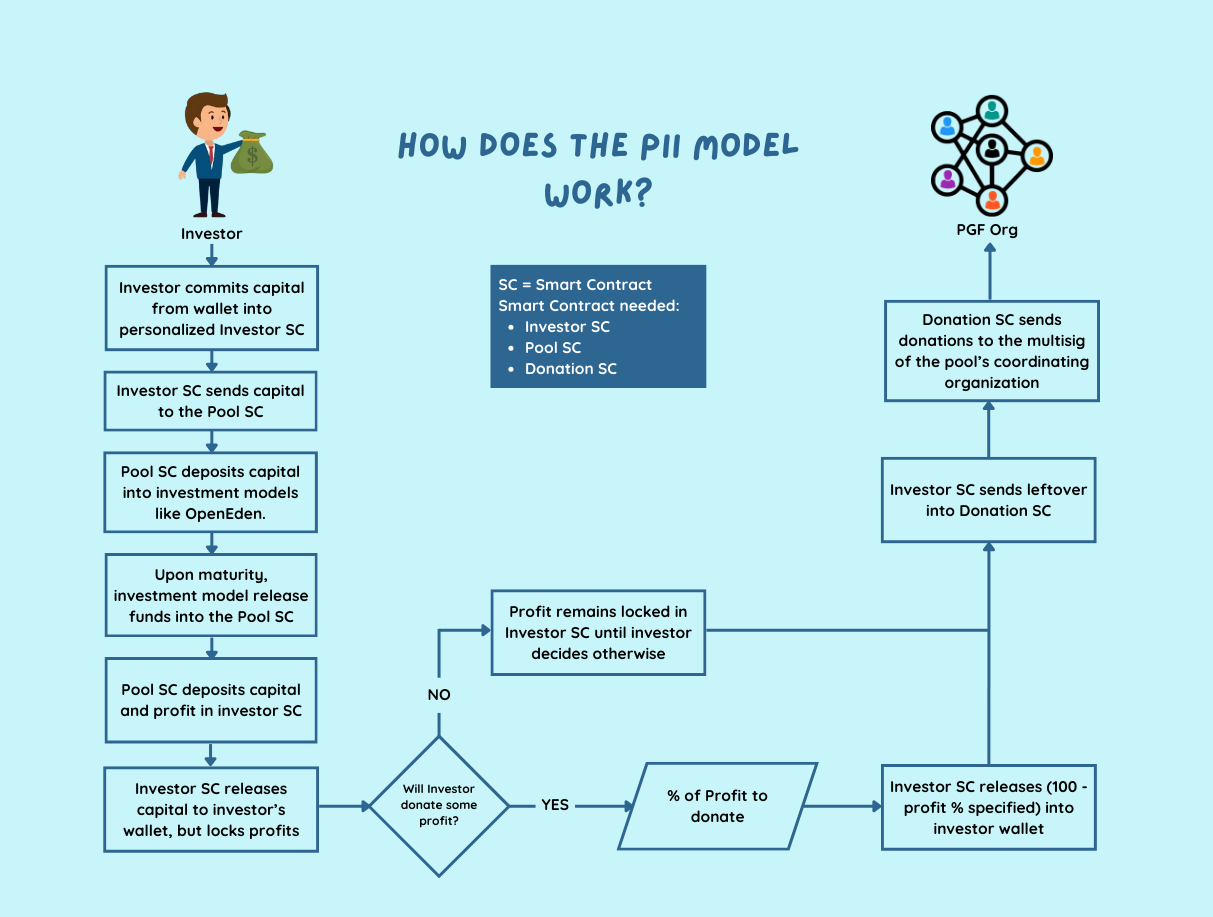

To increase the amount of available PGF, I propose a new model that provides micro-investors with the opportunity to automatically divert a portion of their investment revenue directly to impact PGF matching pools. I call it the PGF-integrated investment instrument, or PII.

A PII is an investment medium that splits returns on committed capital between the investor and PGF. An investor commits capital to the PII for a specified period. Upon investment maturity, the PII locks the profit until the investor donates a percentage after which it releases the leftover profit. The PII then deposits the total donations gathered from all investors into a PGF matching pool.

My initial thought was to implement a voting mechanism where investors could decide on which matching pool profits should go into based on profit percentage donated. However this approach will introduce unnecessary friction The best thing is to decide the pool from onset and build with that in mind.

Two factors determine the underlying investment approach: profit percentage and risk. A general rule of thumb is that a high-risk investment will provide greater returns whereas a low-risk investment will generate low profits. Developers should avoid investments that seemingly guarantee high returns with low risk. Examples of recommended investments include asset-backed tokens (ABTs), bonds, DeFi lending, and short-term treasury bills.

Facilitating capital inflow without reliance on altruism

PIIs reduces the total dependency on altruism by aligning financial success with social good. With the traditional donation model, donors give away money for the love of doing good, whereas PIIs give financial returns in advance for a donation.

Bolstering matching pools

PII shifts the focus from project donations to collective pool funding. Rather than thinning out donations between projects, PII pools profits into matching pools. A decent increase in the matching pool size would definitely increase the matching amount a bottom-ranked project receives.

How it works

-

Capital commitment - Here, investors commit capital into the PII until maturity. However, how they commit capital is dependent on the investment model. A lending investment model would have investors deposit into a liquidity pool upon which the pooled capital is sent to the borrower once complete.

-

Conditional payout - Upon maturity, the PII locks the profit until the investor makes a donation. Depending on the PII, investors could donate whatever percentage they choose except 0% or must donate within a percentage range say 30% to 50%.

-

Pooling of allocated profit - Every donation goes to a pool and will remain there for a certain period to ensure all investors donate. Depending on the PII, profits of investors that failed to donate could be locked until the next round of donation pooling or a certain percentage is automatically donated on behalf of the investor.

-

Allocation of donations - The pooled profit is sent to the organisation coordinating the PGF matching pool. On agreement, the organisation will vest 20% into the PII as capital while 80% goes to the matching pool. The 20% investment will help the organisation become self-sustaining overtime. Investors can choose to reinvest if the returns are satisfactory even after donations.

Hypothetical examples

-

Pinball - Pinball is a fictional ABT PII where investors hold and trade their PIN tokens backed by real estate estate for a certain period. Upon maturity, the gains on the underlying asset are distributed in PIN tokens to all investors who would then donate a percentage. The pooled PIN tokens are then swapped for stables and sent to a PGF matching pool.

-

GIVE - GIVE is a fictitious lending PII where investors deposit funds into lending pools. Once a lending pool is filled, it is closed off and the deposited funds are given out as an over collateralized loan to the borrower. Upon maturity, the loan is repaid with interest which is then redistributed back to investors. The investors then donate a certain percentage of profit which when pooled together is donated as matching funds to a matching pool.

Benefits

-

Encourages a broader range of donors - Although some people do not care about donating to good causes, the entire human race naturally cares about making money. PIIs relies on this psychological knowledge and a little altruism to draw in more investors including the degenerate traders through the stable financial returns offered. Once profit is materialised, the investor automatically becomes a donor.

-

Scales with profitability - More investors equates to more capital inflow for the PII which means more profits and donations. An initial capital inflow of $1k in the first year generating $100 in profits and subsequently $40 in donations could scale to a capital inflow of $100k in the fifth year, generating $10k and subsequently $4k in donations.

Challenges

-

Risk factor attached to investments - No matter the low-risk certainty a particular investment instrument offers, there’s always a chance of the investment going sour. A sour investment is an unfortunate setback for all parties involved. The PII loses trust, investors lose capital, and the matching pool doesn’t get funding.

-

Less interest in what projects are up to - The lingering curiosity of donors on projects donated to with regards to fund usage usually leads to donor fatigue if it is left unsatisfied. A PII eliminates that curiosity because it shifts donations from projects to matching pools.

Next steps

It's common knowledge that ideation is the easiest part of a system development life cycle but implementation is the realest part. So, I decided to implement a really crude manual off-chain PII. I threw US$1,000 into an investment basket of bonds, short-term treasury bills and corporate loans with a 10% return. Upon maturity, I got a US$100 return which I split equally. I reinvested US$1,050 and sent US$50 to another wallet which my mom (who doesn’t know how to use crypto, by the way) holds the passphrase to. If I continue this for the next 10 years without adding more capital, I’ll have US$1,710 as principal and US$710 in the other wallet. Now, imagine executing this with US$50,000–US$100,000.

The next step would be the development of an on-chain PII. Through usage, we’d be able to collect and analyse data to truly determine if PIIs can solve the low funding problem and how long they’ll take to do so in terms of compounding. Unfortunately, I cannot afford the services of a developer so implementation may take a while but I’m open to collaborations whatsoever in building this solution.

This article represents the opinion of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of CARBON Copy.