Decentralising the Planet’s Powerhouse: The Promises of Blockchain-based Solar Production

Louise Borreani and Pat Rawson of Ecofrontiers explore Energy DePIN's potential to advance solar markets with a deep dive into Glow, the protocol driving solar energy expansion.

By Louise Borreani, Pat Rawson | March 24th, 2025

The following article is a guest feature by the co-founders of Ecofrontiers, Louise Borreani and Pat Rawson, sponsored by LFGlow, a decentralised community supporting the Glow Protocol. It evaluates the challenges of today’s solar energy markets and the solutions blockchain-based decentralised physical infrastructure network (DePIN) technologies propose. It uses Glow—one of the highest revenue generating DePIN startups1—as a case study to demonstrate how cryptoeconomic mechanism design can incentivise local and sustainable solar energy production. The article assumes the reader's fundamental knowledge of blockchain systems.

The Solar Market Puzzle

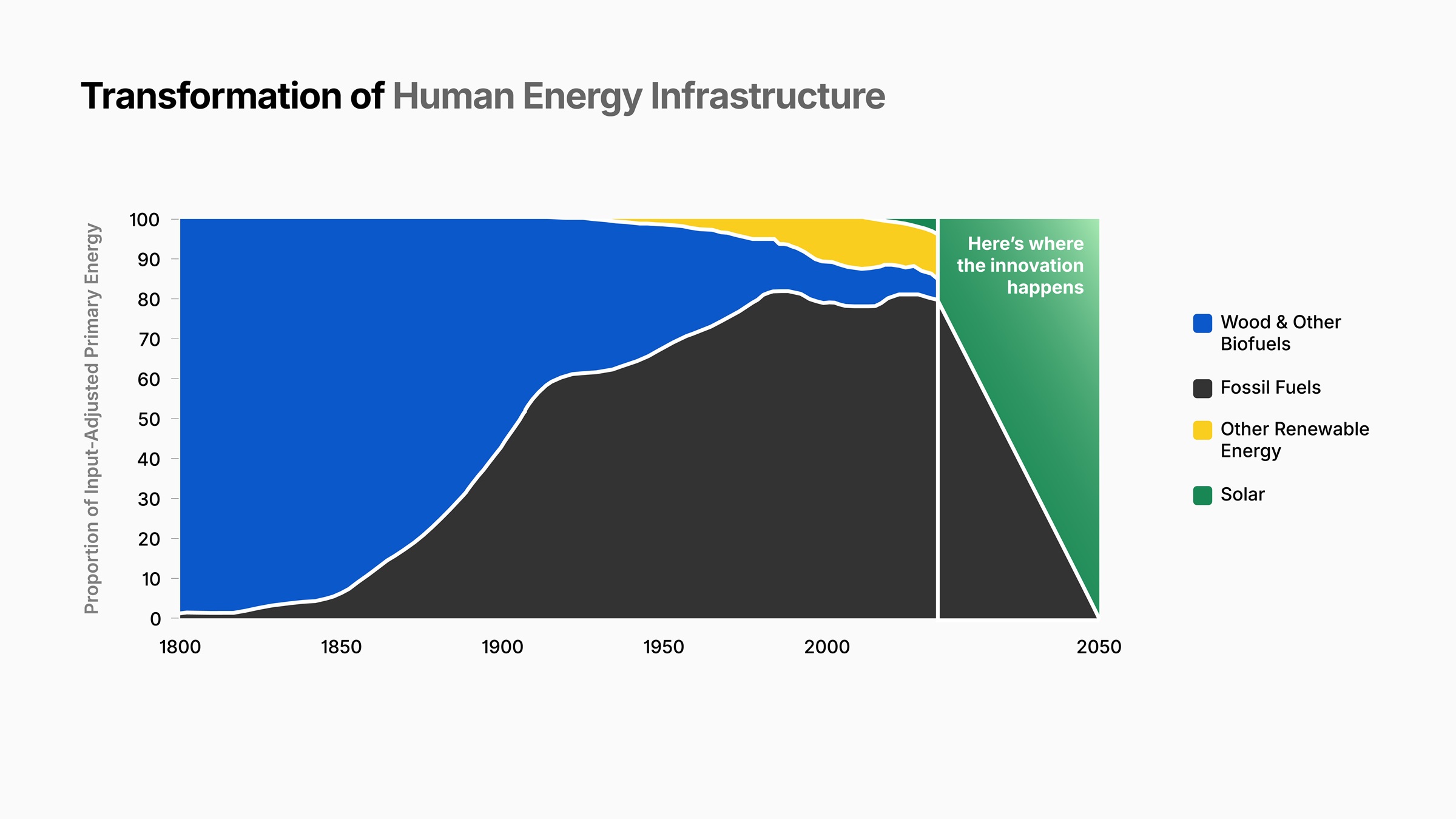

Graphic adapted from Smil, Vaclav. Energy Transitions: Global and National Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2017.

Electricity generation strongly contributes to rising CO2 emissions,2 with coal and oil-based production being the worst culprits.3 Given the central role electricity production plays, and civilisation’s growing hunger for more—e.g., the energy-intensive compute required for AI4—its decarbonisation is non-negotiable.5 As such, global clean energy investment must accelerate significantly beyond its existing $2 trillion in 2024,6 to meet The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recommendation of $4 trillion by 2030 to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.7 The time is now, as every year of underinvestment increases future costs.8

Solar energy—power harnessed from the sun’s radiation, converted into electricity or heat using photovoltaic cells or solar thermal systems—is the frontrunner for these investments. A complete shift to solar-based electricity could reduce global emissions by over 40%.9 To unlock this potential and achieve net-zero targets, a twentyfold increase in solar capacity is required by 2050, or over 600 GW of solar annually from 2030 onwards.10 This ambitious growth trajectory is not without challenge. While solar energy offers an immense promise as the lodestar for a sustainable energy future, its market is rife with structural issues that hamper scalability:

Solar energy, by its nature, competes with itself, a market phenomenon known as "cannibalisation."11 The more solar energy is produced, the lower its marginal value becomes. That is, the additional economic benefit gained by each extra unit of solar production diminishes as supply increases. This dynamic arises in part from solar energy’s learning rate, where increased production leads to lower costs due to cumulative experience and efficiency improvements.12 Paradoxically, this constrains the speed of the renewable transition, as energy investments have traditionally been driven by profit motives rather than cost savings.13 This "solar paradox"—where decreasing production costs reduce long-term profits—restrains distributors and wholesalers who must balance profitability with expanding capacity. This effect is compounded by grid capacity limitations—the maximum amount of electricity the grid can safely transmit and distribute. For example, in the USA, the grid connection queue has grown sevenfold over the past decade, with solar, wind, and battery projects accounting for 95% of the backlog.14

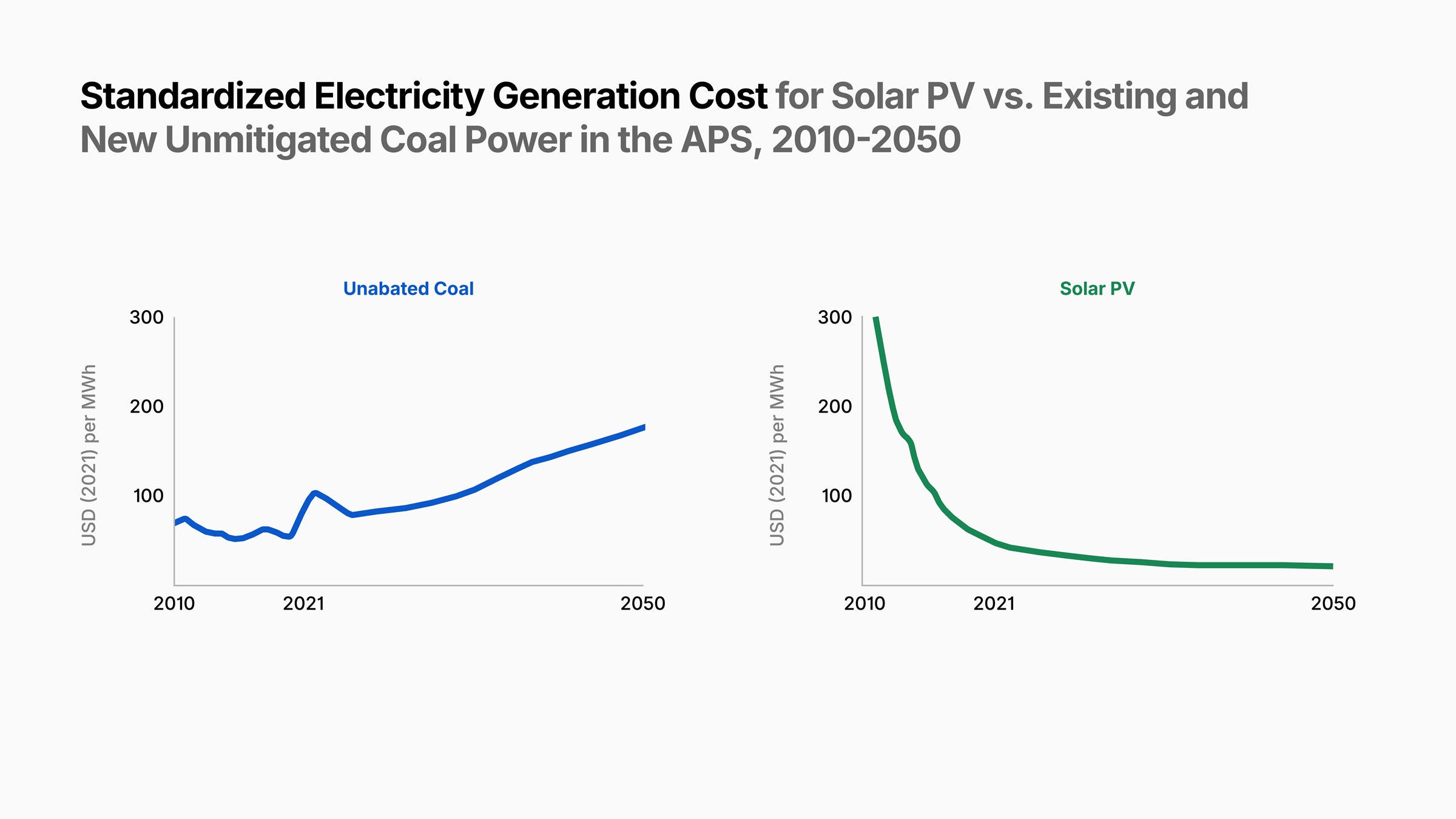

This comparison of levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for unabated coal and solar photovoltaic (PV) in the APS scenario, 2010–2050, showcases the declining costs of solar PV completely outperforming coal over time (measured in USD 2021 per MWh). Graphic adapted from International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2021. Paris: IEA, 2021.

Despite their potential, solar markets fall short from functioning as "pure" markets. These types of markets are characterised by perfect competition where firms can freely enter and exit, products are homogeneous, there is freely available information, and normalised profits. While decentralised finance (DeFi) applications and the broader blockchain ecosystem exhibit these traits, the energy sector diverges significantly from this competitive ideal. Large financial institutions like BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, and Brookfield Asset Management dominate the solar energy investment landscape.15 This concentration is reinforced by government subsidies and incentives, which—rather than fostering broad competition—often favor established investors with the capital and expertise to navigate complex regulatory landscapes.16 These subsidies, along with long-term power purchase agreements and tax incentives, create high barriers to entry for smaller players. As a result, investment in solar infrastructure is shaped more by financial viability and return expectations than by decentralisation, carbon reduction, or consumer cost savings.

The current energy market resembles a jigsaw puzzle due to its high fragmentation and low integration.17 In this jigsaw market, operations are split across distinct silos—generation, transmission, and retail. Energy generation companies focus solely on producing power, while transmission and retail companies often operate independently. This disjointed structure, combined with the absence of real-time data sharing and coordinated operations, suboptimally distributes energy and increases costs for both corporates and consumers. Moreover, regulatory frameworks and jurisdictional differences hamper economies of scale.

Finally, state intervention further complicates the notion of energy as a pure, fully competitive market. Without government intervention, renewables often struggle to achieve the profitability needed to attract private investment.18 As U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission commissioner Mark Christie notes, energy "markets" are largely “administrative constructs” with only some “market-like characteristics”.19 In the EU, half of the member states had state intervention addressing retail electricity prices as of 2020.20 In these nominally free markets, top-down price controls are commonplace.

Energy DePIN’s Game B

When any new technology comes along and proves economically viable, the commercial world into which it is incorporated always changes to one extent or another as a result. This was as true… for the personal computer as for cryptocurrency. … New technologies disrupt established ways of doing things economically as well as technically.

While traditional energy markets often fail to align with free-market principles, emerging innovations such as Decentralised Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePIN) seek to place market dynamics at the core of energy production. By leveraging blockchain-based cryptoeconomic mechanism design, DePIN aims to mitigate the industry inefficiencies inherent to centralised energy systems. In a typical DePIN design, participants contribute physical resources in exchange for rewards—a Web3 adaptation of the sharing economy.21 In this sense, Energy DePINs are to be differentiated from peer-to-peer electricity markets such as Powerledger, Electron, or Pylon Network as they are designed to decentralise and incentivise renewable energy production at scale, ensuring infrastructure is built from the ground up rather than just tokenising energy transactions. DePIN proponents such as David Vorick (CEO & Founder, Glow International) claim that it is apt “at mobilising massive amounts of raw infrastructure. It does it quickly, it does it efficiently, and it does it cost effectively.”22 This claim is well-supported, surpassing conventional expectation:

-

Bitcoin’s compute network has scaled to over 10 million ASIC machines.

-

Filecoin’s decentralised storage network now manages over 10m terabytes of data.

-

Helium now supports a decentralised global data network of more than one million connectivity hotspots.23

These projects have collectively emitted billions USD in tokens to competitively incentivise markets to form around infrastructural production. Their common underlying mechanism design is described as foundational DePIN, an economic strategy modeled after Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work system, which operates according to three key principles:

- A large rewards pool with a fixed inflation rate...

- Distributing proportional rewards on a regular schedule...

- Invoking permissionless competition.24

Energy DePIN is specifically centered on the foundational production and deployment of renewable energy assets. Energy DePIN complements and enhances existing foundational systems like Bitcoin, which uses energy to produce a decentralised money—BTC—valued in the USD trillions today.25

Case Study: Glow

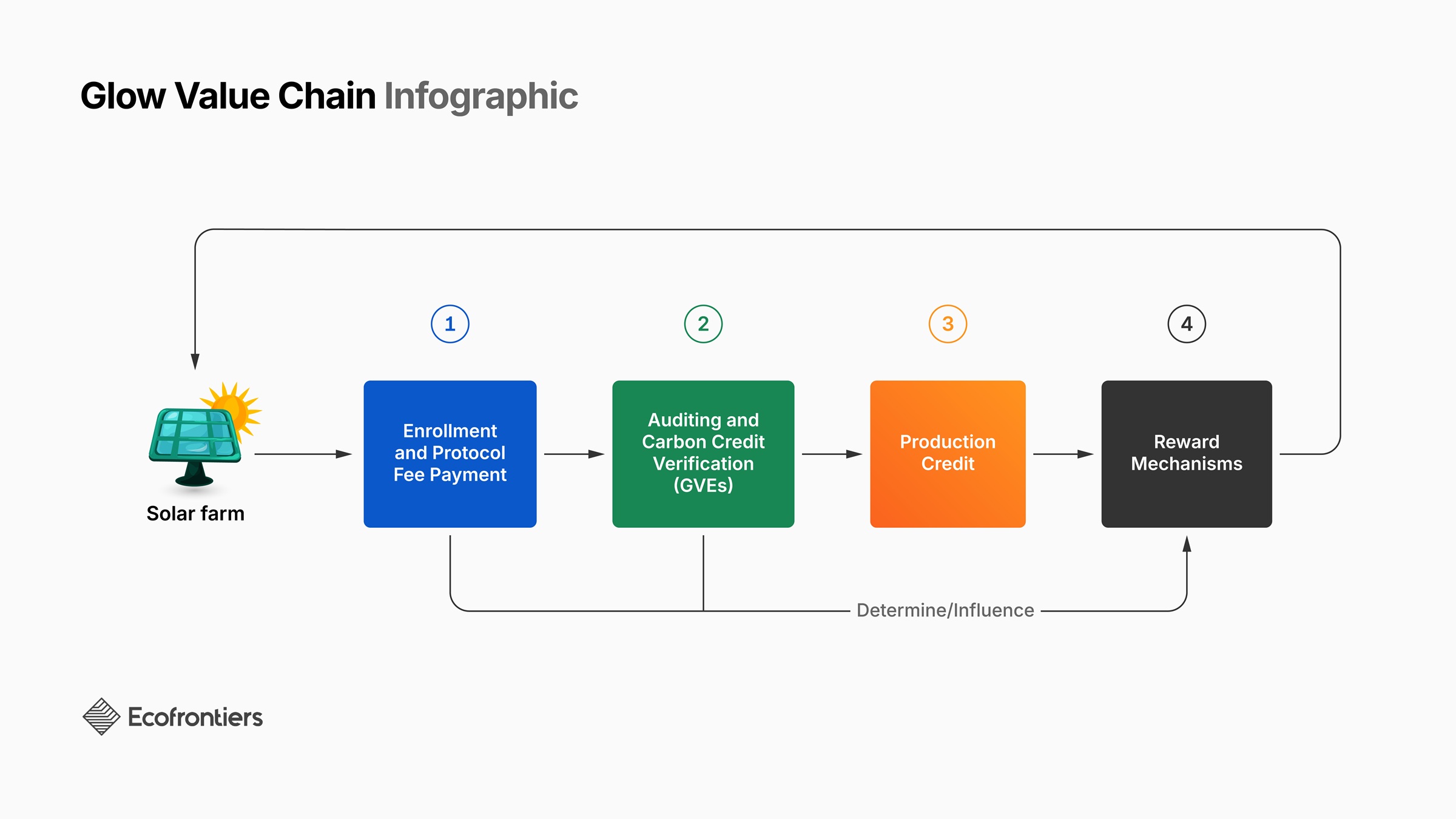

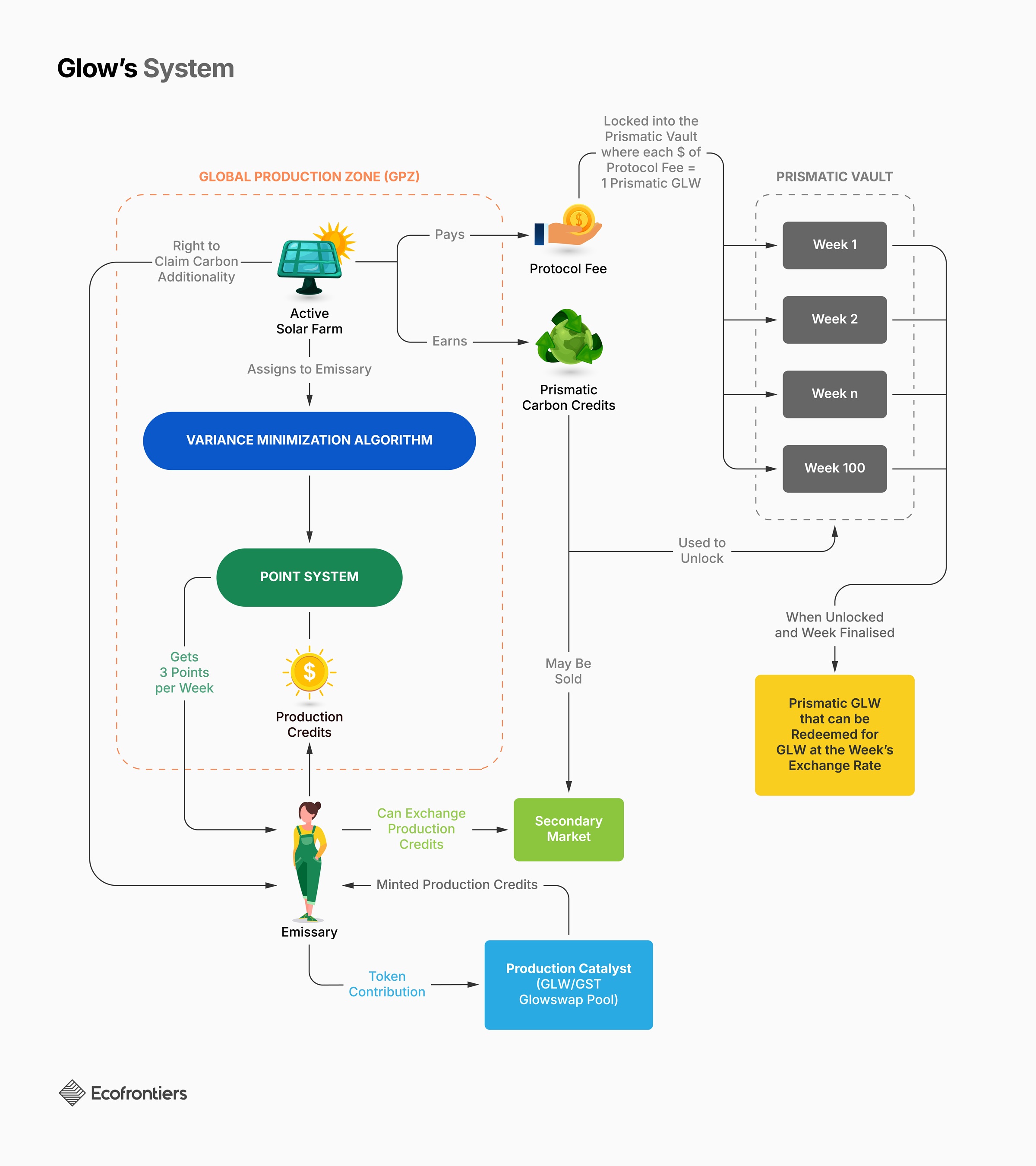

Simplified flow of the Glow system, where solar farms get rewards proportional to their protocol fee and carbon credit production. Farms are certified weekly by Glow Verification Entities (GVEs).

Having outlined the big picture of solar industry structure and Energy DePIN, it is now pertinent to explain how these macro dynamics play out at the organisational level. The most prominent26 Energy DePIN example today is Glow, a decentralised solar energy protocol that rewards farms based on their electricity revenue contributions and carbon credit production, reinvesting revenues into new solar projects to create a self-sustaining growth cycle. As a case study, Glow offers insights into their broader implications for the future economics of energy systems. At certain points in this section, the authors simplify Glow for the purposes of the reader. A full description will soon be available Glow v2 Whitepaper.27 At a high level, Glow’s cryptoeconomic design, a.k.a its protocol, can be divided into seven components:

1. Solar Farm Enrollment and Protocol Fee

At the core of Glow’s economic model is the commitment of solar farms to give 100% of their electricity revenue (paid in USDC: a tokenised US-dollar equivalent) to the protocol as a fee. This is a fundamental joining requirement that ensures that solar farms have long-term skin in the game. With this collectivisation mechanism, Glow’s primary constraint becomes the number of solar farms it can attract.28 It serves to align the individual financial incentives of solar farms with the protocol’s collective goals of increasing solar capacity and generating carbon avoidance credits. That is, Glow’s carbon credits represent emissions reductions achieved by avoiding fossil fuel-based energy production through renewable substitution.29

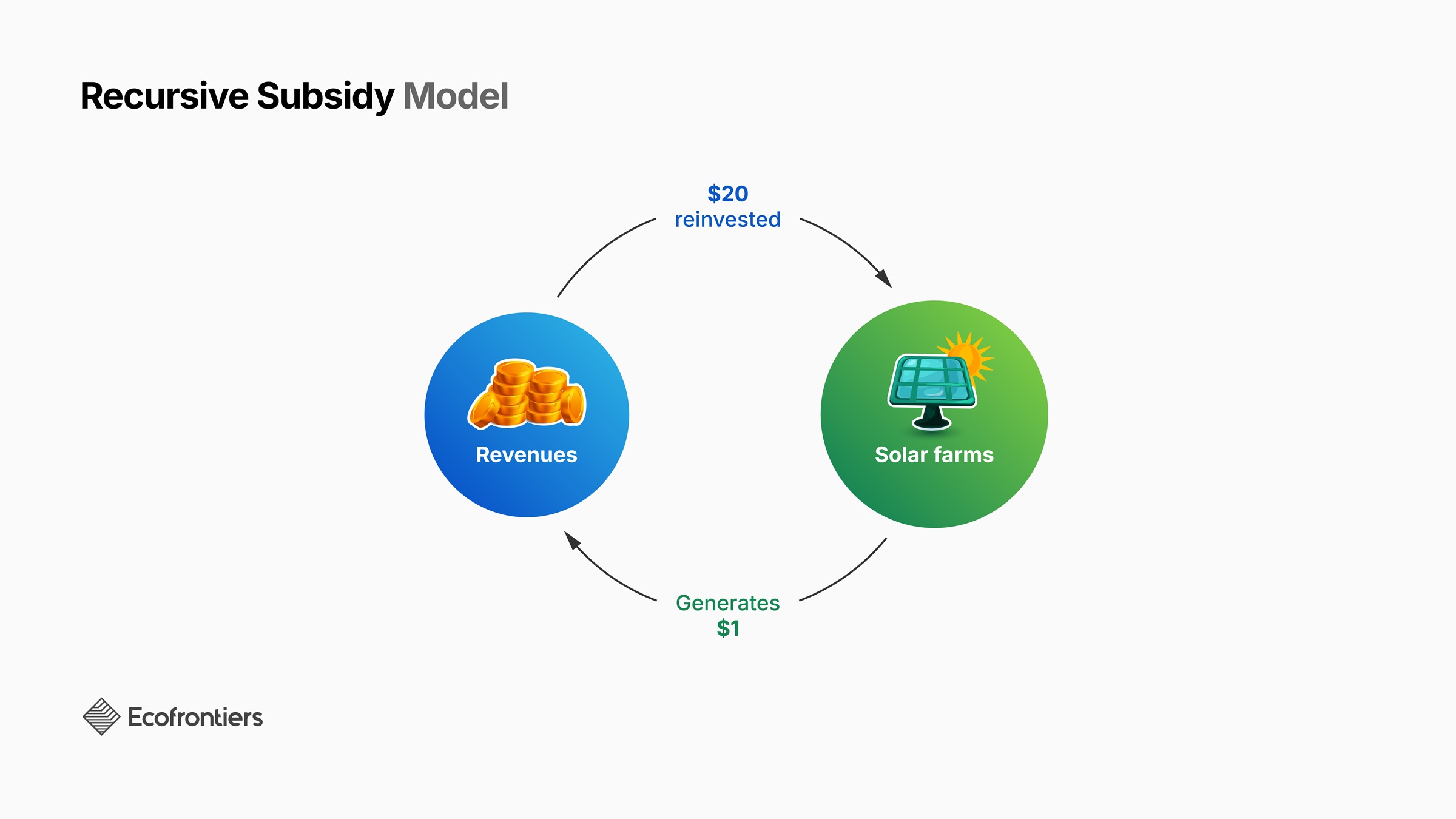

Glow’s protocol proposes a recursive subsidy model, where the revenue generated by solar farms is reinvested into the construction of new solar projects, creating a compounding effect on solar infrastructure development. Glow claims that this creates a multiplier effect, where every dollar spent on initial construction could result in an estimated $20 in additional solar infrastructure over time.30

2. Certification and Carbon Credit Generation

Like the traditional carbon industry, Glow Verification Entities (GVEs)—previously known as Glow Certification Agents (GCAs)31—audit the electricity output of solar farms to certify the carbon credits they generate. Certification ultimately aims to ensure that the credits are additional, or that emissions reductions would not have happened otherwise without Glow’s protocol. In other words, the credits from Glow-funded solar farms must be verifiably linked to real, extra emissions reductions, with one carbon credit equivalent to one tonne of avoided CO2 emissions. This is not necessarily the case in some traditional carbon markets, and is the most frequent culprit behind accusations of greenwashing.

To maintain the integrity of the certification process, Glow’s governance elects up to five GVEs—corporate entities tasked with independently auditing Glow’s production zones, defined as designated areas within the Glow protocol where solar farms receive allocated resources and incentives to support energy generation and carbon credit production. Their role is not to defend or promote Glow but rather to provide accurate appraisals and ensure that all claims made by the protocol are verifiable. Given their broad and ongoing responsibilities, GVEs operate at an institutional level rather than as individual auditors.

A Veto Council consisting of elected protocol delegates32 oversees the certification process. This separate authority exists to ensure that GVEs conduct rigorous audits and that violations of criteria result in delayed or withheld rewards to solar farms. This separation of powers is a traditional principle of good governance design that helps provide accountability across different branches of an organisation.

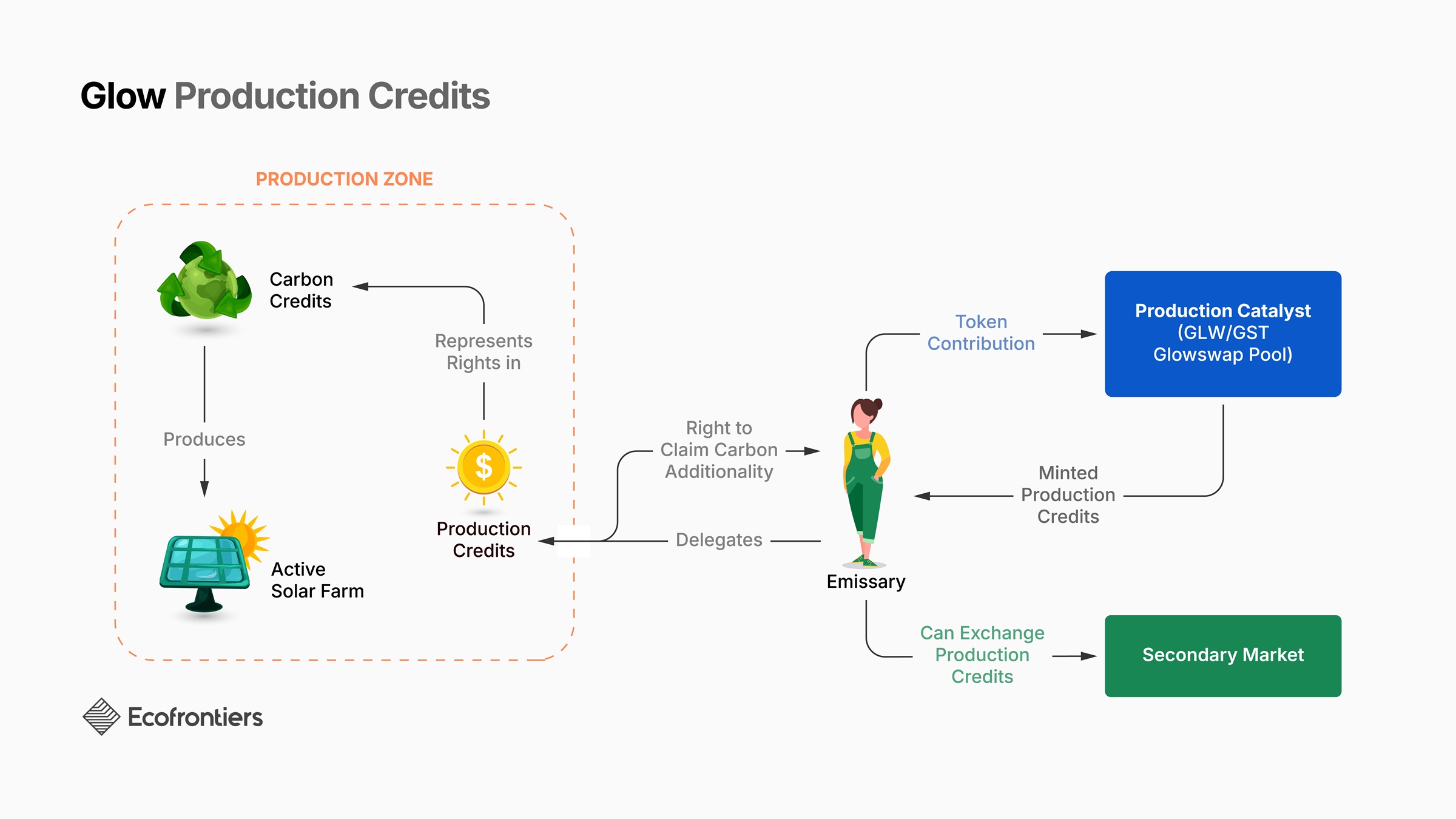

3. Glow Production Credits

Unlike traditional carbon credits, which are typically one-off purchases to offset emissions, Production Credits represent ongoing rights to non-transferable carbon avoidance credits produced by specific solar farms.

While Glow’s carbon credits were originally sold in a Dutch auction format, a recently proposed update (Q1, 2025) renders them non-transferable. With this update, the only way to obtain carbon credits is through ownership of Production Credits, a new type of perpetual forward-looking asset that assigns the right to direct the allocation of GLW tokens toward specific solar production zones. Unlike traditional carbon credits whose one-time purchase retroactively finances a past emissions reduction, Production Credits perpetually finance carbon avoidance through their rights to claim carbon additionality.

By holding and delegating Production Credits to a solar farm, users called emissaries decide where Glow’s token rewards go, ensuring that funding supports the most effective projects. On the opposite of traditional carbon programs that offer generic credits with little transparency, Glow links credits to specific solar farms, providing real-time power data and verifiable impact.33 Production Credits can be obtained by minting them34 or buying them from existing holders. Their value depends on how well solar production zones convert incentives into real energy output.

4. GLW Token and Lock Mechanism

Glow has its own fungible token, GLW, which is allocated as a delegated reward to solar farms and funds governance operations. A key feature of GLW’s design is its interaction with Production Credits. To mint Production Credits directly from the protocol, users must provide liquidity to a decentralised GLW market—in Web3 nomenclature, a liquidity pool—which will transfer their withdrawal rights to a smart contract that manages Production Credit issuance. This contract then eliminates those withdrawal rights, ensuring that the deposited funds remain permanently locked in the system. This mechanism keeps value circulating within Glow’s protocol, stabilizing demand for GLW while preventing price crashes and excessive speculation.

5. Glowswap Decentralised Exchange

To keep the market for Production Credits and GLW liquid and stable, Glow operates its own Automated Market Maker (AMM)—i.e. a digital marketplace where one asset can be exchanged for another—called Glowswap.35 The AMM introduces various decentralised financial lending features to keep the market dynamics healthy and active, such as liquidity borrowing, which allows traders to borrow from the public liquidity pool and use it to create private liquidity pools that only they can exchange with.36 Through its lending features, Glowswap ultimately helps ensure that debt-based financing is always available for solar farms when liquidity is needed.

6. The Global Production Zone

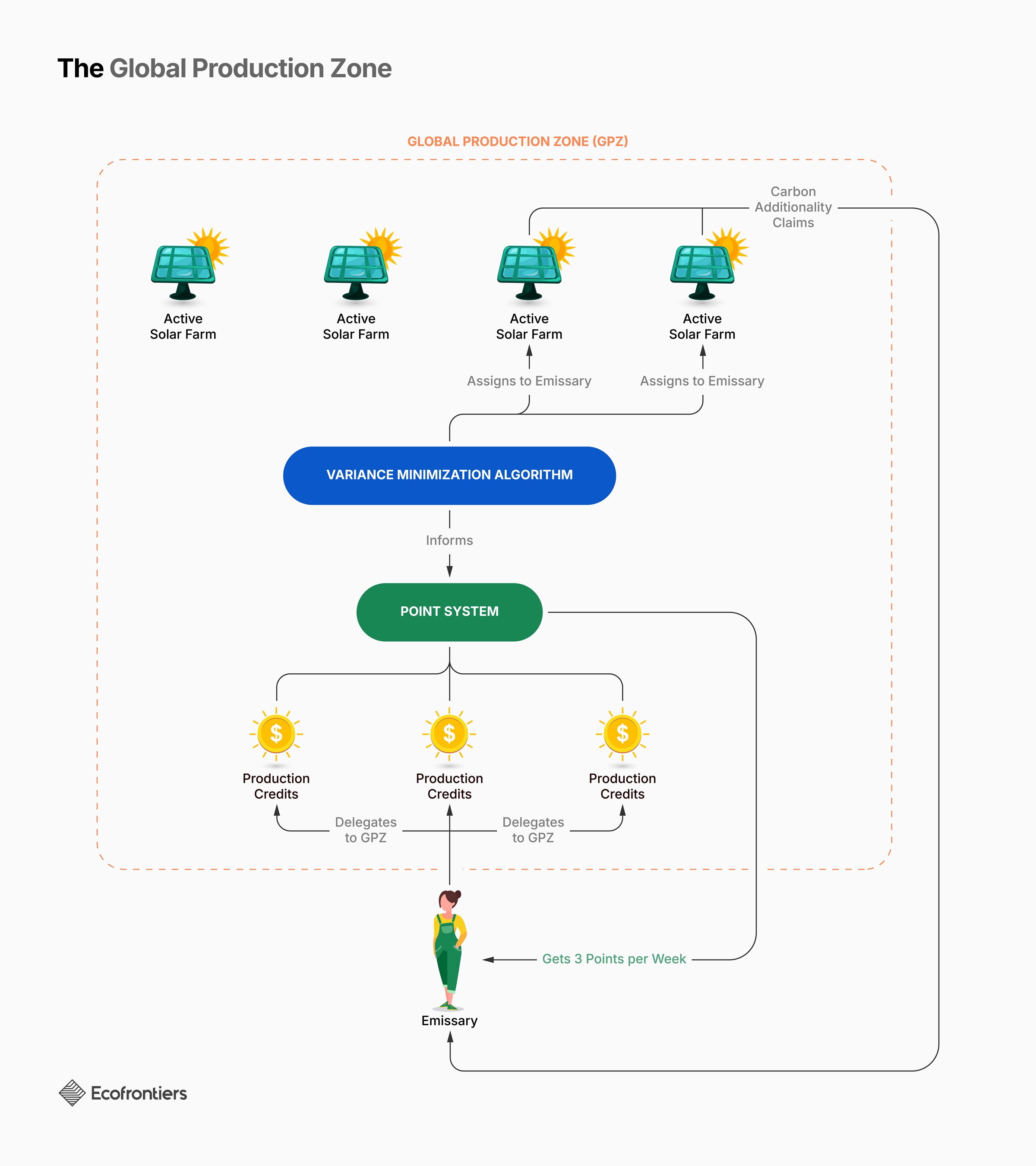

In this example, an emissary delegates three Production Credits to the Global Production Zone, which entails four active solar farms. They are rewarded three points per week for doing so. The variance minimisation algorithm uses the number of points gathered by the emissary to assign them two solar farms of equivalent weight—in other words, the algorithm ensures a fair and balanced allocation of farms to the emissary by distributing their Production Credits across projects of similar impact, preventing disproportionate exposure to underperforming farms. The emissary can then finally claim carbon additionality associated with those two farms, from which they will receive photos, audits, and live data.

The Global Production Zone (GPZ) is the most competitive area within Glow, designed to maximise carbon emission reductions by directing incentives to the most impactful solar farms—especially those in regions where solar projects are least likely to be funded without additional support. Emissaries who delegate their Production Credits to the GPZ accumulate points, which determine their assigned set of solar farms. A fair distribution algorithm ensures that incentives are allocated dynamically, prioritising farms with the highest climate impact. Unlike other production zones, which may focus on different political or impact goals and generate outputs like Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), the GPZ exclusively produces carbon offsets. Overall, the GPZ functions as a geolocalised arbitrage zone which dynamically reallocates carbon benefits based on Production Credit’s delegation and solar farm performance.

To prevent unfair distributions, solar farm weights are reassessed periodically to ensure emissaries who have delegated equal amounts of Production Credits are not disproportionately assigned underperforming projects. The GVEs oversee this reassessment schedule.

7. Reward Mechanisms and Long-Term Independence

Solar farms in Glow receive GLW token rewards based on their electricity revenue and carbon credit production. The latest protocol update introduces a final component: the prismatic reward system, which exists to make rewards more dynamic and market-driven. Each week, solar farms earn prismatic GLW based on their protocol fees paid. Each farm receives one prismatic GLW per dollar paid in protocol fees. As prismatic GLW is tradable in the secondary markets, these assets function as a prediction market37 for future rewards, allowing farms to optimise their earnings. Once a week finalises, prismatic GLW can be exchanged for GLW tokens, with the final exchange rate determined at that time by the protocol based on the performance of solar farms over the week. Hence, farms producing above-average carbon credits receive greater rewards, ensuring the most impactful projects of the moment get the most funding—thus incentivising solar farms to continuously improve.

Data from Glow’s rewards dashboard38 shows that solar farms consistently earn GLW rewards equivalent to a significant portion of their electricity revenue—in most cases providing a meaningful boost beyond electricity sales alone. For example, at the time of writing, one of the top-performing solar farm in Rajasthan, India, that joined Glow on October 2, 2024,39 has earned a total of 772K GLW (approximately $3M) and $147K in USDC in rewards, averaging 36K GLW (~$140K) and 7K USDC per week. Additionally, the $1.58M protocol fee contributed by the farm has been reinvested by Glow into the construction of new solar capacity, as per the protocol’s recursive subsidy model.

This same prismatic strategy is used for carbon credits. Unlike traditional carbon credits, which are fixed at issuance, prismatic carbon credits dynamically adjust their value based on real-time carbon performance. Each week, these credits are issued in proportion to a solar farm’s verified carbon reduction, with stronger-performing farms receiving a greater share. Importantly, prismatic carbon credits are essential for unlocking prismatic GLW rewards. The amount of prismatic carbon credits required corresponds to the protocol fees paid, ensuring that solar farms must demonstrate carbon impact to fully access their earnings. If a farm lacks sufficient prismatic carbon credits, it must acquire them from others in the market, while farms with surplus credits can sell them. Because the total supply of prismatic carbon credits each week is precisely calibrated to match the protocol fees paid, no excess is created. This system aligns financial incentives with sustained carbon efficiency while maintaining a balanced and liquid market for prismatic carbon credits.

Full diagram of the Glow protocol, where solar farms receive rewards in GLW and USDC proportional to their initial contribution of the present value of 10 years of their electricity revenue upfront and carbon credit production. For purposes of simplification, this diagram doesn’t include mention of auditing and governance mechanisms.

Piecing It All Together: From Puzzles to Legos

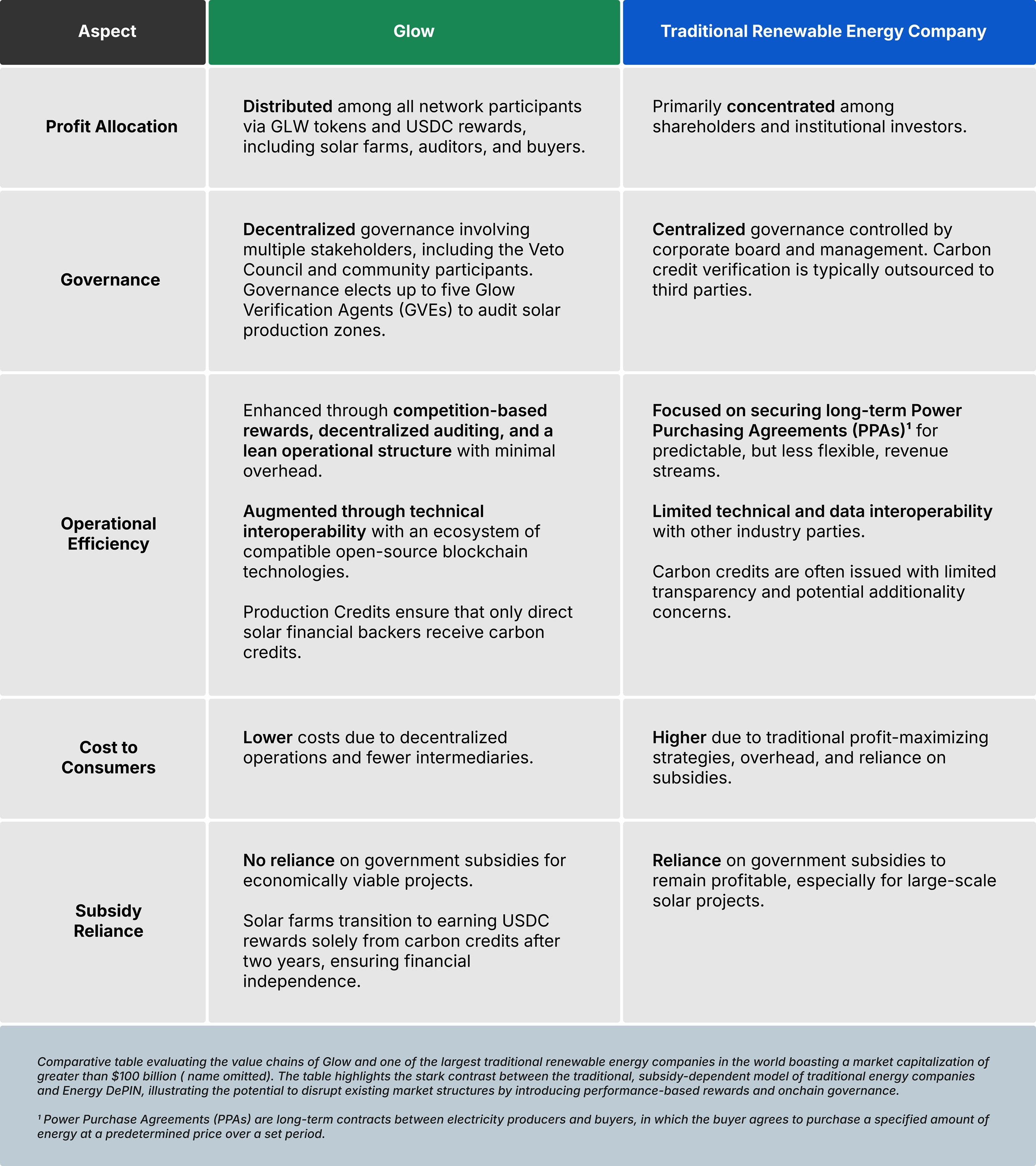

At a glance, speculatively comparing Glow—and Energy DePIN at large—to the solar market’s jigsaw puzzle is like comparing a finely-tuned orchestra to a scattered jam session. Glow’s orchestrated yet decentralised system stands in stark contrast to the traditional solar market, where players act largely independently and against each others’ interests. Instead, Glow seeks to align the costs and benefits of energy production through:

Eliminating economic deadweight loss

At its heart, Glow seeks to eliminate subsidies for already profitable solar farms while boosting those farms that need assistance. Its performance-based, collectivised reward system incentivises efficiency above all else. Nevertheless, solar farms that produce more energy or optimise resources earn greater rewards, establishing a meritocratic base that fosters true competition.

Value chain optimisation through decentralised governance

Decentralisation is a cornerstone of Glow’s governance model, where different platform stakeholders collectively participate in key processes such as audits and certification. Unlike traditional industry, which tends to operate behind closed doors, all transactions, audits, and governance actions are recorded onchain, providing an immutable and public record of operations.40 These generalised blockchain affordances, in principle, ensure a high level of trust and accountability. It also invites a smaller and more diverse coalition of market actors to participate due to the absence of the types of informational asymmetries closed-door negotiations between large institutional players tend to propagate. As a decentralised crypto-institution, Glow and other Energy DePIN projects like it hold the potential to put pressure on the institutional concentration of power in the energy sector to perpetuate a more dynamic market where small-scale producers thrive.

Cost efficiencies from usage of interoperable, open-source blockchain technology

As mentioned prior, much of the increased coordination costs in the energy industry come from its incapacity to share data and other resources for intra-industry coordination. Furthermore, the inherently inoperable nature of tokenised financial products can function as modular "building blocks" for constructing innovative cryptoeconomic systems beyond what a protocol may have originally intended. Bridging Energy DePIN such as Glow with traditional and existing DeFi mechanisms opens an innovative mechanism design frontier for novel renewable energy-backed financial products. Production Credits illustrate how decentralised platforms can foster financial innovation with tokenisation. In the future, we may see innovations like synthetic derivatives that automatically hedge against weather-related energy output fluctuations, peer-to-peer lending protocols allowing stablecoin borrowing against energy-backed assets; or at its most basic tokenised carbon credits can be embedded in the circuits of energy usage associated with databases themselves, just as some blockchains already automatically mitigate their emissions today.41

As traditional energy markets face the consequences of their puzzle structure, Energy DePIN is already proving its strong potential to redefine how energy markets are structured while simultaneously advancing broader macroeconomic goals of environmental accountability and carbon neutrality. Imagine a society where financial transactions inherently support verifiable clean energy and carbon neutrality, finally giving all economic participants a straightforward mechanism for “cleaning” their consumption and spending patterns. It’s hard to see how a never-ending jigsaw puzzle where market actors must constantly adjust to the rules of the game or even go as far as to change the rules in their favor can compete with the automated Lego-like systems that blockchain-based innovation favors. Whether or not it can succeed in the face of an existing industry—an industry with every incentive to push against consumer cost reduction in favor of organisational profit-seeking—is yet to be seen.

About Glow ☀️

Glow, an Ethereum-based solar infrastructure protocol, revolutionizes the decentralized electric grid by rewarding solar farms with GLW tokens for their electricity production and USDC for their carbon credits. More than a protocol, Glow is a green energy movement to replace the entire dirty grid with 100% renewable clean energy. Individuals and Commercial Solar Farm prospective customers should contact: hello@glowlabs.org.

About Ecofrontiers 🌳

Ecofrontiers is a research agency producing theoretical and technical knowledge for a green institutional transition. The team offers new and established Web3 projects research, consulting, and advisory services.

Website | X | The Green Crypto Handbook

References

1 DePIN Ninja2 Glow (2023). Glow: A Cryptoeconomic System for Producing High Additionality Carbon Credits, p. 1

3 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 5

4 Kindig, Beth (2024). AI Power Consumption: Rapidly Becoming Mission Critical

5 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 8

6 IEA (2024). Overview and Key Findings. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024/overview-and-key-findings (Accessed on: 11/03/2025)

7 IEA (2021). Net Zero by 2050. A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (Accessed on: 11/03/2025)

8 Ibid

9 Glow (2023). Glow: A Cryptoeconomic System for Producing High Additionality Carbon Credits, p. 1

10 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 30-31

11 James, Ben (2024). Solar Will Get Too Cheap to Connect to the Power Grid

12 James, Ben (2024). Solar Will Get Too Cheap to Connect to the Power Grid

13 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong

14 James, Ben (2024). Solar Will Get Too Cheap to Connect to the Power Grid

15 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 96

16 Hasan, S. M. Z. (2024). Bidding for Bangladesh: The Suitability of Auctions for Renewable Energy. National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR).

17 Sengupta, Shayon & Jain, Tushar (2024). The Great Energy Coordination Problem

18 Private equity and institutional investors often seek ROI between 10% and 15% for renewable energy projects. In some cases, especially for riskier projects or those in emerging markets, investors might expect returns as high as 20%.

19 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 37

20 Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong, p. 61

21 Wikipedia (n.a.). Sharing economy

22 Vorick, David (2023). Why Glow Excites Me

23 Bane, Dylan (2024). DePIN’s Glow Up: Incentivizing the Development of Solar Farms

24 Bane, Dylan (2024). DePIN’s Glow Up: Incentivizing the Development of Solar Farms

25 CoinGecko

26 As of 2025, Glow is growing at a staggering 50% month over month.

27 Bane, Dylan (2024). DePIN’s Glow Up: Incentivizing the Development of Solar Farms

28 Publishing date unknown. Authors of the article could consult an unpublished, private version.

29 Enright, Niall (n.a.). My assessment of the Oxford Offsetting Principles.Available at: https://www.sustainsuccess.co.uk/my-assessment-of-the-oxford-offsetting-principles (Accessed on: 14/01/2025)

30 Vorick, David (2023). What is Glow?

31 At the time of writing, there were two Glow’s GCAs: One from Glow’s internal operational team, and another owner of Araya Auditors. Source: Glow (n.a.). Meet the Glow Certification Agents. Available at: https://glow.org/gcas (Accessed on: 05/02/2025)

32 Glow (2023). Glow: A Cryptoeconomic System for Producing High Additionality Carbon Credits, p. 2

33 Vorick, David (2025). n.a.. X. Available at: https://x.com/davidvorick/status/1888974252788810224?s=46&t=_WsUi1np5oVUM3T08vcXkQ (Accessed on: 14/02/2025).

34 Glow calls this specific Glowswap pool the Production Catalyst. See Glowswap definition in section 5.

35 Glow (n.a.). GlowSwap Introduction. Available at: https://glowswap-docs.vercel.app/ (Accessed on: 11/03/2025)

36 Glow (2025). Fragmentation Is All You Need.

37 A prediction market is a marketplace where participants trade contracts based on the outcome of future events, with prices reflecting the collective probability of those outcomes.

38 Available at https://www.glowstats.xyz/farms (Accessed on: 21/02/2025).

39 Farm 445. Available at https://www.glowstats.xyz/farms/Farm%20445%2C450 (Accessed on: 21/02/2025).

40 Glow (n.a.). Audits. Available at: https://glow.org/audits (accessed on 10/12/2024)

41 Celo Foundation (2021). A Carbon Negative Blockchain? It’s Here and it’s Celo.

Bibliography

-

James, Ben (2024). Solar will get too cheap to connect to the power grid

-

Sengupta, Shayon & Jain, Tushar (2024). The Great Energy Coordination Problem

-

Christophers, Brett (2024). The Price Is Wrong

-

Lazard LCOE (2024). Levelized Cost of Energy

-

Jones, Dave (2024). Tweet

-

Rosenow, Jan (2024). Tweet

-

Ember (2024). Tweet

-

Dunleavy, Tom (2024). Tweet

This article represents the opinion of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of CARBON Copy.